The need to protect those who, by trade, had to approach the sick during an epidemic arose as early as the 14th century, in conjunction with one of the plague epidemics that struck Europe.

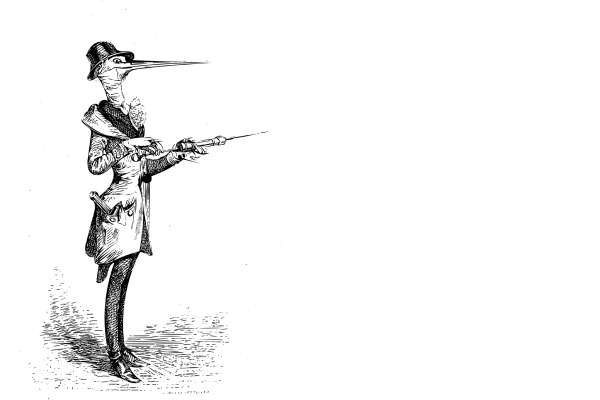

In the 17th century, the doctors who cared for the victims wore a costume that has since taken on sinister connotations: they dressed from head to toe and wore a mask with a long bird's beak.

This "costume" is usually attributed to Charles de Lorme, a physician who managed to cure many European royals during the 17th century, including King Louis XIII and Gaston of France, son of Marie de' Medici. He described an attire consisting of a coat covered in scented wax, breeches tied to boots, a shirt tucked into pants, and goatskin hat and gloves.

Plague doctors also carried a rod that enabled them to strike (or ward off) plague victims. The garb of the chief was particularly unusual: plague doctors had to wear goggles and a mask with a nose about twenty centimeters long, shaped like a beak, with only two holes-one on each side next to the respective nostril-but which was sufficient to breathe, and which carried along with the air the effluent of herbs contained along the beak.In fact, plague doctors filled their masks with teriaca, a compound of more than 55 herbs and other components such as viper flesh powder, cinnamon, myrrh and honey.

De Lorme thought the beak shape of the mask could give the air enough time to soak in the protective herbs before hitting the doctors' nostrils and lungs.

The reason behind these beak-shaped plague masks was due to a mistaken belief about the real nature of the disease. There were various theories, the most popular being that an unfavorable conjunction between Jupiter and Saturn or contaminated water was to blame, but most were convinced that it was bad smells and dirty air, called "miasma," that transmitted the disease. Thus, the purpose of the mask was to keep bad smells away, preserving the wearer from contagion. For this same reason, only north-facing windows were considered safe for ventilation, and doctors' masks were filled with scented plants.

The real cause of the plague was not discovered until 1894: Yersinia pestis, a bacterium that could be transmitted from animals to humans, contact with contaminated fluids or tissues, and the inhalation of infected droplets released by the sneezing or coughing of people with pneumonic plague.

Not long after, in 1897, Austrian surgeon Johann von Mikulicz Radecki described a closer ancestor of what we know today as a surgical mask, composed of a layer of gauze. In those years, German hygienist Carl Flügge had shown that normal conversation could spread bacteria-laden droplets from the nose and mouth, confirming the need for an effective mask for the face. This initiated awareness of the danger associated with human exhalation as a cause of surgical wound sepsis.

Others credit the first person to wear a surgical mask to French surgeon Paul Berger while operating in October 1897. Berger had been alerted by some cases of suppuration after otherwise clean operations with an assistant suffering from an alveolar abscess. A similar situation arose a few months later when Berger himself was afflicted with dental periostitis. He also noticed drops of saliva projected from the surgeon or assistant when they spoke. Aware of Carl Flügge's discovery of pathogens in saliva, he decided to protect his operations from this form of contamination, and in October 1897 he began to wear: "a rectangular wrap of six layers of gauze, sewn on the lower edge to his sterilized linen apron (he had a beard to protect) and the upper edge held against the root of his nose by cords tied behind his neck."

Over a period of fifteen months he became convinced that the incidence of infection had been reduced.

The surgical mask must now be worn by health care workers during surgery and some other health care procedures to capture microorganisms present in liquid droplets and aerosols from the wearer's mouth and nose.

Evidence supports the effectiveness of surgical masks in reducing the risk of infection among other health care workers and in the community. For health care workers, safety guidelines recommend wearing a face-tested FFP2 respiratory mask instead of a medical face mask around influenza patients to reduce the wearer's exposure to potentially infectious aerosols and airborne liquid droplets.

The use of face masks (and spacing) proved to be the best defense strategy against the uncontrolled spread of Sars-Cov-2, prior to the arrival of vaccines.