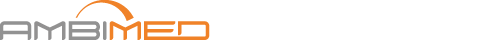

Meningitis

Meningitis is an inflammation that affects the membranes surrounding the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), which has two origins: bacterial or viral. The bacterial form is the most dangerous for humans. Whereas, generally, viral meningitis does not lead to serious consequences.

Bacterial meningitis can be caused by different types of bacteria: Meningococcal, Pneumococcal, and Haemophilus.

Although the new vaccines show great promise, meningococcal infection continues to be reported in both industrialised and developing countries, where universal vaccine coverage is non-existent and antibiotic resistance is increasingly common.

CAUSES

Meningococcal meningitis is caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Neisseria Meningitidis. This bacteria causes significant morbidity and mortality in children and young adults worldwide, both through epidemic or sporadic forms of meningitis and/or septicaemia.

At the nucleotide level, Meningococcus shares 90% homology with N. gonorrhoeae or N. lactamiea, and the virulence of the bacteria is influenced by multiple factors.

It is a challenging bacteria that dies within hours on inanimate surfaces and is an encapsulated aerobic diplococcus. At least 13 distinct meningococcal groups have been defined on the basis of their immunological reactivity and the structure of the capsular polysaccharides. These serogroups are: A, B, C, E-29, H, I, K, L, W-135, X, Y, Z and Z '(29E). However, only six serogroups (A, B, C, W-135, X, Y) cause life-threatening disease.

TRANSMISSION

Meningitis is a disease that is transmitted from an infected person to healthy person via the respiratory route, through droplets of saliva and nasal secretions released while talking, coughing and sneezing. Meningococcus, which predominantly infects humans, has developed multiple mechanisms that allow it to spread, adapt to, and colonise the mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory tract.

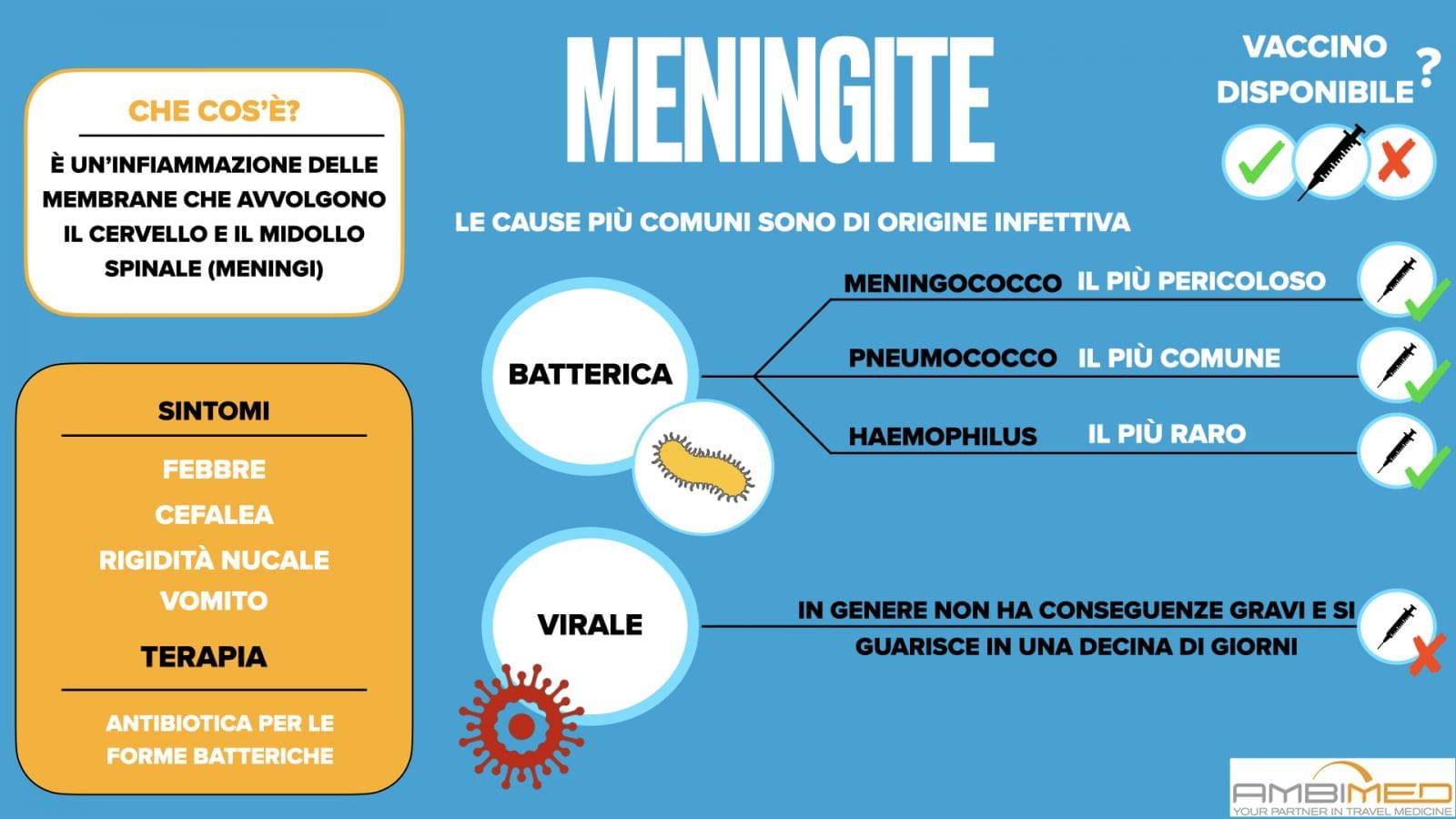

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

Bacterial meningitis is the most frequent form of CNS (Central Nervous System) infection, with a variable annual incidence. The worldwide incidence varies greatly depending on the geographical region. Approximately 500,000 to 1,200,000 invasive meningococcal diseases occur each year, leading to 50,000 to 135,000 deaths.

In Italy and Europe, most cases of meningococcal meningitis are mainly attributable to serogroup B and serogroup C, although an increase in serogroup Y has also been reported in recent years. Serogroups A and W135 are prevalent in the rest of the world, particularly sub-Saharan Africa.

Serogroup A was the main agent of invasive meningococcal disease in Europe before and during World Wars I and II, while serogroup B has been prevalent in Europe since 1970, and South America since 1980. Epidemic outbreaks caused by the W-135 and Y serogroups have emerged more recently during the 21st century. In addition, there has also been a change in the age groups affected by invasive disease, with an increase in the incidence of serogroup Y in the elderly and a decrease in serogroup C in adolescents.

The epidemiological trend of the invasive disease has remained virtually unchanged in Africa, where serogroup A is still the most prevalent, with an annual incidence of 10-20 cases per 100,000 population. Epidemic outbreaks occurring during the dry season imply an attack rate of more than 1,000 cases per 100,000; very recently, serogroups X and W-135 have had a major impact in terms of morbidity and mortality.

In Australia, the incidence of meningococcal disease is more than 3 cases per 100,000 population. In most American and European countries there is generally a low level of endemicity. In 2011, 29 European countries reported 3,808 confirmed cases of invasive disease. The incidence of invasive disease caused by serogroup B in Europe accounted for 0.5 cases per 100,000 population. Italy reports the lowest incidence rate of 0.25 cases per 100,000.

SYMPTOMS

Meningococcus is normally found in the upper respiratory tract, such as the nose and throat, of about 30 percent of the population, often asymptomatically. In fact, the greatest likelihood of being infected comes from contact with healthy carriers (only 0.5 percent of disease cases are transmitted by people who are ill).

Generally, the incubation period for meningococcal meningitis is 3 to 4 days, but it can vary from 2 to 10 days.

Meningitis initially presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue, drowsiness, asthenia, and headache. After about 3 days, the symptoms tend to get worse, with nausea, vomiting, fever, photosensitivity, and characteristic nuchal stiffening.

The infection can evolve into three clinical situations: sepsis (meningococcaemia), meningitis, and sepsis with meningitis.

Meningococcaemia is observed as an isolated clinical presentation in 10-30% of patients, in the absence of signs and symptoms of meningitis. Meningitis represents the most frequent clinical presentation and is characterised by the onset of high fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, photophobia, and delirium. Meningococcal infection can also be responsible for pericardial infection; purulent or immune-complex arthritis, conjunctivitis, panophthalmitis, and urogenital tract infections are also possible.

In new-born babies, the symptoms may not be very obvious and manifest in constant crying, irritability, and loss of appetite.

DIAGNOSIS

In addition to the identification of typical symptoms, diagnosis is based on laboratory tests. After performing a blood culture, a lumbar puncture test for examining cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) must be carried out. The use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on blood or CSF may allow more rapid identification of the responsible microorganisms.

TREATMENT

Bacterial meningitis is a medical emergency. As such, it should be treated as quickly as possible with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Antibiotics should be chosen based on the epidemiological criteria and characteristics of the patient. Generally, the treatment of choice involves the combined use of cephalosporins with ampicillin.

PREVENTION

Primary prevention is based on the preventive administration of the meningitis B vaccine and meningitis A, C, W, Y vaccine. Several types of meningitis vaccines are available in Italy, and are also recommended in the National Vaccination Plan.

Each and every one of us will come into contact with the meningitis bacteria at least once in our lives. However, only a relatively small percentage of people go on to develop the disease (about 200 people per year), compared to the thousands and thousands of healthy carriers.

Anyone can contract meningococcal disease, but certain groups of people are at higher risk. Meningitis vaccine is the most effective preventive strategy for protecting the entire population, with a special focus, however, on the more vulnerable, such as children and adults with compromised immune systems.

The Vaccine Calendar strongly recommends that children are vaccinated against meningococcal B and meningococcal C during the first few years of life, as their immune systems are not yet fully formed, and transmission is facilitated by the close social contact, typical among this group.

Other individuals who should be considered for vaccination are adults with diseases that weaken the immune system, such as genetic diseases, oncohematological diseases, diabetes, or people taking immunosuppressive therapy. People who work in settings that favour the transmission of the bacteria, such as health care workers and teachers, are also advised to take the meningitis vaccine.

Although meningococcal disease is widespread globally, the "meningitis belt" of sub-Saharan Africa has the highest infection rates in the world. Travellers who spend a lot of time with local people in the meningitis belt, especially during outbreaks of meningococcal disease (December to June), have the highest risk of contracting the disease. People attending the Hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia are also at increased risk, which is why preventive meningitis vaccination is required by the country's National Authorities.

As well as vaccination, good hygiene practices are also essential:

- Wash your hands frequently

- If soap and water are not available, cleanse hands with hand sanitiser (containing at least 60% alcohol)

- Never touch your eyes, nose or mouth with unwashed hands

- Cover your mouth and nose with a handkerchief or sleeve (not your hands) when you cough or sneeze

- Try to avoid contact with people who are ill.

Contact surveillance

Contact surveillance is a strategy outlined by Health Authorities to control infections and possible epidemic outbreaks. It consists in tracing, identifying and possibly dealing with contacts that are considered significant for the index case, i.e., the person who is infected.

Careful evaluation must be carried out depending on the individual case, but usually a close contact is identified as:

- A cohabitant (this also includes occupants of the same classroom or shared offices/enclosed spaces)

- Anyone who has often slept or eaten in the same place as the infected person

- Anyone who has had contact with the infected person's saliva, such as through kissing or eating utensils

- Health care personnel directly exposed to respiratory secretions.

Source: Epicentro

Bibliography & Sitography

Hmwe H. Kyu , John Everett Mumford, Jeffrey D. Stanaway, Ryan M. Barber, Jamie R. Hancock, Theo Vos, Christopher J. L. Murray and Mohsen Naghavi. Mortality from tetanus between 1990 and 2015: findings from the global burden of disease study 2015. BMC Public Health, 2017.

G. Gabutti, a. Stefanati, P. Kuhdari. Epidemiology of Neisseria meningitidis infections: case distribution by age and relevance of carriage. Review of department of Medical Sciences, university of Ferrara, Italy. J prev med hyg 2015; 56: e116-e120

Nadine G. Rouphael and David S. Stephens. Neisseria meningitidis: Biology, Microbiology, and Epidemiology. HHS Public Access, Methods Mol Biol. 2012; 799: 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-346-2_1.

Moroni M., Spinello A., Vullo V. Manuale di Malattie Infettive. Edra LSWR, Masson, 2014.

Bartolozzi G. Vaccini e Vaccinazioni, Seconda Edizione. Masson 2015.

Rugarli C., Obiass M., Medicina interna Sistematica, Quinta Edizione. Masson 2015; 1585-1586