Lyme disease

Lyme disease (also known as Lyme borreliosis) is a bacterial infection transmitted by ticks to humans, which is now seeing a rise in cases even in areas of the world that were previously free of the disease. It is unclear whether this is due to environmental and ecological changes, or increased medical and public awareness of the infection, which has led to more reports.

In fact, since it was recognized in 1976, Lyme disease has become the most common animal vector infection, particularly in North America, where there are more than 30,000 cases reported each year.

CAUSES

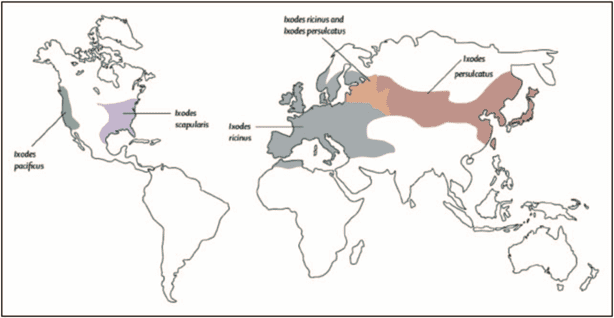

Lyme disease is a multi-system zoonotic disease caused by the spirochaete bactera Borrelia burgdorferi. It is transmitted by ticks of the species complex Ixodes ricinus, Ixodes scapularis, andIxodes pacificus.

TRANSMISSION

Lyme disease is mainly transmitted by Ixodes nymphalis ticks, which feed in late spring and early summer. Rodents, including white-footed mice and squirrels, are the preferred host and maintain the life cycle of the infection. White-tailed deer are the primary mating host for adult Ixodes ticks.

3 to 32 days after the bite, the bacteria migrate from the surrounding skin, spreading via the lymphatic system or bloodstream to the organs.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

There are several subspecies of Borrelia, which vary in geographical distribution and clinical symptoms. In Europe, including the United Kingdom, the prevalent organisms are B. afezelii and B. garinii, although infections with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. spielmanii and B. bavariensis can also occur. In North America, Lyme disease is found in the Pacific Northwest and Canada.

The life cycle of the spirochete determines the seasonality and geographical distribution of Lyme disease. Ticks mature into larvae and nymphs that feed during the hot summer months, consequently, the incidence of cases also reflects the local climate.

The disease is geographically expanding from high-incidence areas to neighbouring, low-incidence areas.

Within the endemic regions, smaller geographical areas of very high incidence have been found. The age-related risk of Lyme disease is determined by the time spent at risk of tick exposure, which creates a bimodal distribution of children aged 5-15 years and adults of 45-55 years.

SYMPTOMS

The evolution of Lyme disease proceeds in three stages.

Most patients develop early stage disease (also called early localised disease), with erythema migrans, a characteristic infectious rash that develops around the site of the tick bite. Early stage disease may be localised to the skin or the organism may spread via the circulatory system, causing early disseminated Lyme disease with constitutional symptoms that can involve the skin, nervous system, heart, or joints.

Within weeks or months, some untreated patients can progress to the advanced stage of the disease, which mainly presents as Lyme arthritis. Almost all patients with early Lyme disease can be treated with a short course of oral antibiotic therapy.

However, early stage disease is not always recognised or clinically evident. In the advanced stage of the disease, most patients can also be successfully treated with antibiotic therapy, but a minority suffer from antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis, which requires other management strategies.

After erythema migrans, neurological involvement is the second most common clinical feature in the UK and Europe. About 5% of individuals with untreated erythema migrans will develop neuroborreliosis, which usually occurs 4-6 weeks after tick exposure.

More than 95% of patients present within 6 months of infection, and any neurological stmptoms during this period are called "early" neuroborreliosis.

Only 25% of patients with neuroborreliosis recall a tick bite and approximately 50% report a localized skin reaction; consequently, the absence of a history of tick bite or rash does not exclude the diagnosis.

Late-onset and chronic Lyme disease

Late neuroborreliosis is defined as clinical symptoms that last for more than 6 months with evidence of active infection. This is rare and comprises less than 2% of neuroborreliosis cases. It has mainly been observed in continental Europe.

European clinical reviews suggest that the disease process is a form of CNS (Central Nervous System) vasculitis, with persistent inflammation of vessels caused by chronic infection.

With very few cases and overlapping cohorts, it remains difficult to clearly define and differentiate early CNS neuroborreliosis and late CNS neuroborreliosis.

Despite advances in the understanding of its clinical features, diagnosis and treatment, Lyme disease has been the source of much miscomprehension and anxiety. This misunderstanding may result from the rapid emergence of the vector-borne infection, its multisystem characteristics, and potential threat to the nervous system.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is based on clinical evaluation combined with serological tests.

Enzyme immunoassay is highly sensitive in established Lyme disease, and immunocompetent individuals with disseminated neuroborreliosis almost invariably have a strong IgG response, although acute-phase (IgM) and late-phase (IgG) antibody titers may also be useful when conducted 2 weeks apart.

Early in the disease there is lower sensitivity, which can lead to false negatives. However, symptoms of neuroborreliosis usually begin several weeks after the initial bite, which means circulating antibodies should be present.

TREATMENT

Most cases of neuroborreliosis resolve without treatment within 3-6 months.

Antibiotics rapidly improve the patient's symptoms, particularly pain. Penicillin, doxycycline, ceftriaxone, and cefotaxime are all effective for early neuroborreliosis. Neuroborreliosis with CNS involvement is most often treated with intravenous ceftriaxone, but several studies have shown that oral doxycycline is just as safe and effective as ceftriaxone in dealing with all the forms of neuroborreliosis.

Doxycycline has the advantage of being an oral preparation, but is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation.

There are no current recommendations for the use of corticosteroids.

Most patients recover completely with treatment, although this may take several months. Sometimes the disease can cause permanent damage, to cranial or peripheral nerves, for example.

An extended treatment course is recommended for immunosuppressed patients, people with severe disease, extrapulmonary infection, and individuals who have received inappropriate initial therapy. Early appropriate therapy is a major factor in reducing mortality.

Only a few studies on antibiotic resistance have been conducted. Resistance to therapeutic substances from the group of fluoroquinolones, macrolides, tetracyclines or rifampicin has only been observed in isolated clinical cases.

PREVENTION

To avoid infection, it is essential to take precautionary measures to avoid tick bites when visiting endemic areas. The best way to avoid tick bites is to:

- Keep to well-trodden paths and trails in forested areas;

- Walk in the middle of pathways, to avoid bushes, plants, weeds and grass;

- Avoid sitting on the ground;

- Wear long-sleeved clothing and long trousers;

- Apply an insect repellent that contains DEET;

The early and correct removal of ticks is another good prevention strategy. Tick bites that go unnoticed are more likely to transmit the bacteria because the insect may have been attached to the skin longer, which greatly increases the risk of transmission. Removing a tick within 24 hours usually prevents infection, while the risk of infection increases when the tick has been attached for more than 48 hours.

Antibiotics are not recommended for tick bites, unless skin alterations are observed. There have been attempts to develop a vaccine, but the results have been disappointing, and there are currently no vaccines available for human use.

Bibliography:

C. Eldin a, A. Raffetin b, K. Bouiller c, Y. Hansmann d, F. Roblot e, D. Raoult f,∗, P. Parola. Review of European and American guidelines for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Review 0399-077X/© 2018 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Masson SAS.

Arbour AG, Benach JL. 2019. Discovery of the Lyme disease agent. mBio 10:e02166-19. Arturo Casadevall, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Amy Louise Ross Russell, Matthew Dryden,Ashwin Arnold Pinto, Joanna Lovett. Lyme disease: diagnosis and management. Ross Russell AL, et al. Pract Neurol 2018;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2018-001998.

Robert T. Schoen. Lyme disease: diagnosis and treatment. 1040-8711, 2020 Wolters Kluwer Health. Volume 32, Number 3, May 2020.